Good Fences Make Good Neighbors: The What and Why of Boundaries

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’

Excerpt from The Mending Wall, by Robert Frost

“Good fences make good neighbors.” This is what the narrator’s neighbor says to him in Robert Frost’s classic poem The Mending Wall. Every year in the spring the two farmers walk the stone-walled boundary between their two properties, and they mend the fence where fallen boulders have left gaps. The fence is important because it keeps the cows from wandering into the neighbor’s field and getting hurt or causing damage. But the fence isn’t so high that it shuts out all communication or relationship between the farmers. The poem makes clear that the two neighbors have different philosophies on where and why to put the wall, but they both can agree that well-maintained boundaries are crucial to their continued good relationship with each other as well as to the well-being of their individual properties.

Though we rarely have a physical wall to mark the boundary line, boundaries are important in any relationship. They help us protect ourselves while allowing us to maintain connection with others. In psychological terms, boundaries help us balance our need for authenticity with our need for attachment (see this video for an excellent explanation of why these are such fundamental needs). Authenticity is our need to be ourselves: to know who we are, to be in touch with our bodies and emotions, and to express ourselves freely. Attachment is our need to be connected to one other: to form families and societies, to find belonging, to work together. Without careful attention, these two needs can become unbalanced and at odds with each other. We can end up prioritizing the needs of others at the expense of our own, or we can pursue what we want so doggedly that we find ourselves alone. The type of boundaries we have and the places we decide to put them can tell us a lot about how well-balanced our needs for authenticity and attachment are.

Let’s look a little closer with this illustration. Imagine you love to garden and you’ve recently planted all of your summer vegetables. The first seedlings have begun to poke their heads above the ground, and you begin to worry that rabbits or squirrels will get to them before they have a chance to grow into stronger, hardier plants. So you buy some mesh fencing with small enough holes to keep out the rodents, and you build a fence around the seedlings high enough to keep the pests from jumping over. You decided on mesh and not solid material because you still need the seedlings to be exposed to enough sunlight and wind for them to become mature.

Our relational boundaries are a lot like the fence around this garden. Just as the seedlings need protection from pests who could cause them damage, we need protecting from threats to our emotional and relational needs. Consider our need for privacy. If you had no door on your bedroom door frame, and your family did not follow the social norm of knocking before entering, you would constantly be worried that your dad, or sister, or kids could walk in at any time (your kids may do that anyway, but that’s another story). It would make it hard to feel comfortable changing or doing whatever else requires the privacy of your own bedroom. We need those physical (door) and social (knocking) boundaries to protect our need for privacy. Too few or too weak boundaries threaten our sense of autonomy and expression.

But, lest you think we’ve averted danger completely, too much of a good thing can be dangerous too. In the same way that the mesh fence provided protection to the seedlings while still letting in the sun and the wind, we need our boundaries to be flexible enough so that we still let others in too. If our fences are 10 feet tall and made of iron, we are deprived of connection with others, and we can start to wither. If you’re so preoccupied with your need for privacy that you never share details of your life with your friend or you never open up about how much your brother means to you, you rob yourself of the nourishing effects of intimacy and connection.

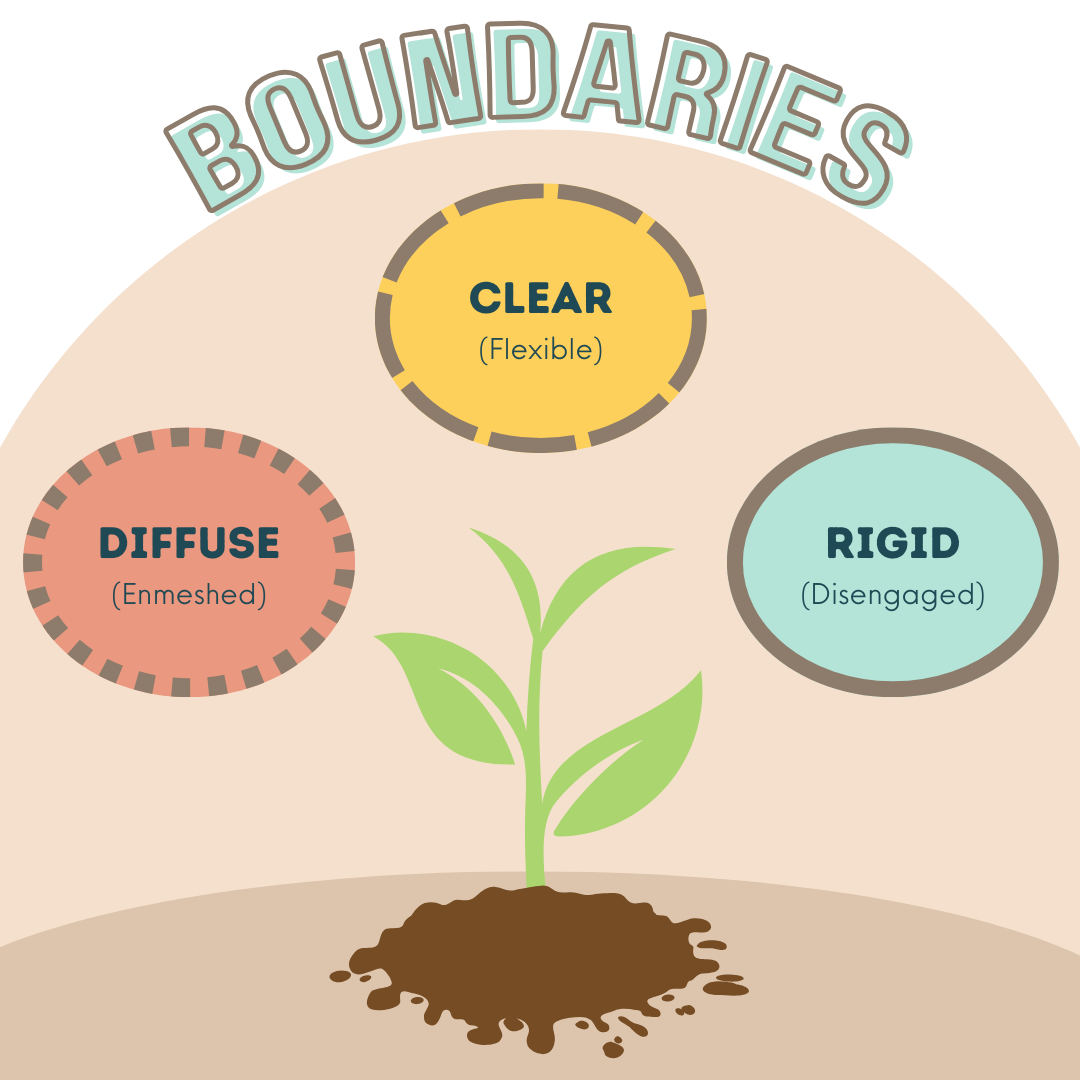

Boundaries that are non-existent or too weak are called diffuse, and they can lead to enmeshment. In other words if the boundary between self and other is eroded, it will be hard to tell where one person’s needs end and the other’s begin. Those two people are enmeshed. This tends to happen with people-pleasers who have a hard time saying no and who put their needs aside to show up for others. On the other end of the spectrum, we have rigid boundaries which are characterized by disengagement. People with rigid boundaries are stuck in self-preservation mode. The boundary between self and other is so strong that it prevents the honest communication needed for intimacy to be possible. This tends to happen in people who are fiercely self-reliant, often because they have had so many moments of relational unsafety that they had to take care of themselves. They tend to sacrifice the need for intimacy for the safety of not risking rejection or abandonment. The meshed fence from our garden analogy is what we want to shoot for, and we call it a clear boundary. There is a clear distinction between two individuals but they are also able to be clear with one another about their emotions and needs. They can be close without being swallowed by each other. There’s a sort of dance that emerges. Both partners are able to transition back and forth fluidly from a state of connection to a state of autonomy. They can navigate back and forth without becoming stuck.

If you’re new to the idea of boundaries or if you’re just now realizing the importance of having clear boundaries, you may be wondering what to do with this information. Start by taking stock of the boundaries in your close relationships and the boundaries you have with yourself. Walk that fence line and see which parts of the wall need mending. The same phrase appears twice in Frost’s poem: “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall and wants it down.” Take a look at your walls, has something eroded your boundary in a place where it needs to be fortified? Are there places where your wall is much too high and formidable that could use some “wanting down”? The first step is noticing where the mending is needed. How to mend it takes lots of learning and practice. When it comes to emotional and relational work like this, we can often have this fantasy of learning it once, tying our development in a neat bow, and moving on to the next thing. But this is ongoing work. It’s not a place you arrive at; it’s a journey of recalibration that requires regular tune-ups and adjustments. Consider talking about it with your therapist if you have one, or reach out to us at the Couch Method to find someone who can help you keep good fences and good neighbors.